The Cork Manifesto

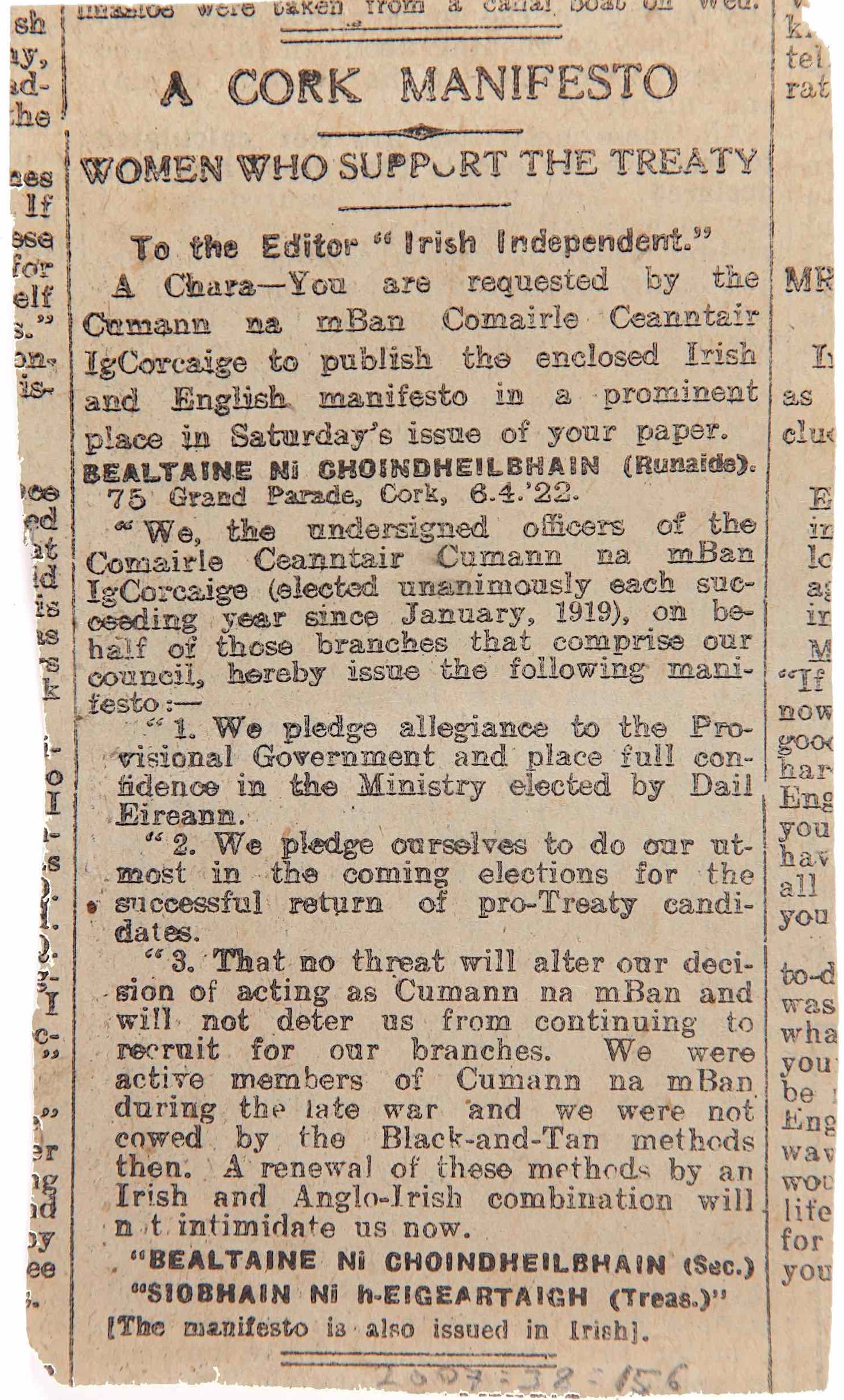

The 6th April 2022, marks the 100th anniversary of the issue of the ‘Cork Manifesto’ in The Cork Examiner. This press cutting is one item in the extensive Conlon Collection held by Cork Public Museum. Dan Breen, Curator of Cork Public Museum for this centenary commemoration, provided his insight on some of the key items in this collection. He explained that it is an important source due to its range, including its local material.

This was part of a public conversation took place in partnership with Cork City Libraries Decade of Centenaries Programme ‘It Seems History Is To Blame’.

Cork City Libraries’ 2022 programme is book-centred.

‘It Seems History is to Blame’ is a quote taken from James Joyce’s Ulysses. This programme ‘seeks to attempt to understand what happened and why, and will, perhaps, offer a chance to learn lessons for our own time.’

You can view their upcoming programme here.

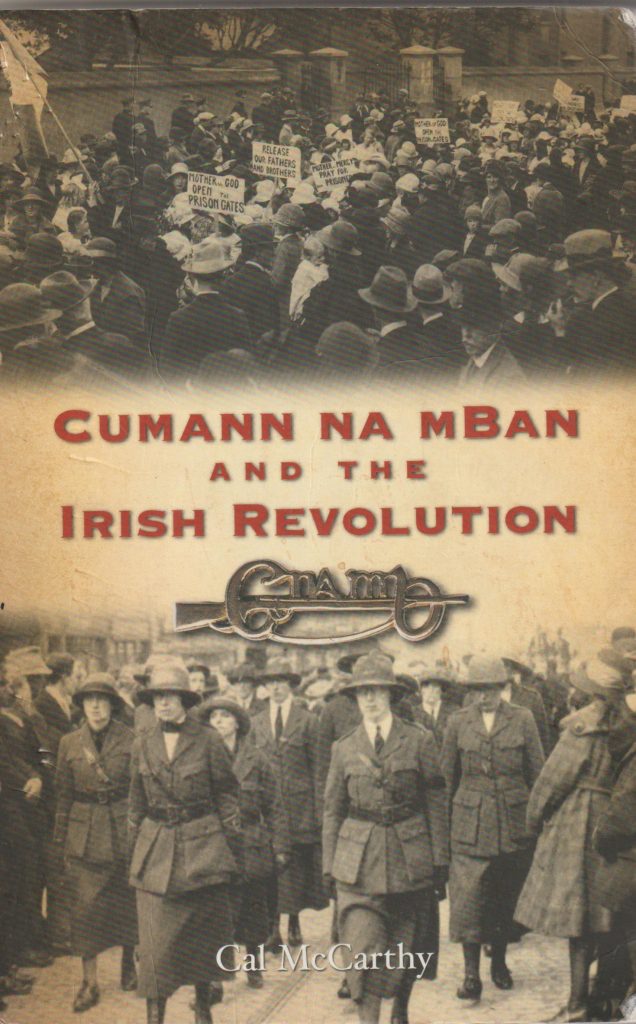

The 2022 programme examines how ‘ordinary people’ recalled events. This special Mná100 Centenary event was a live streamed discussion chaired by Dr Sinéad McCoole, Curator Mná100 and featured panellists, Dr John Borgonovo (School of History, University College Cork), Cal McCarthy (The Michael Collins House Museum, author of Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution, The Collins Press, 2007), Dan Breen (Cork Public Museum), Anne Twomey (Shandon Historical Society), and Councillor Colette Finn (Cork City Council’s Women’s Caucus).

The event was held in Cork City Library, The Mall.

David O’Brien, City Librarian in Cork City library welcomed the Mná100 event:

In commemorating the Revolutionary Period 1920-1923, Cork City Council hopes to learn more about contemporary society by understanding how we have been shaped by the people and events of the past. The focus is to honour the resilience, courage, and heroic efforts of the citizens of Cork as they rebuilt their city following the Burning of December 1921 and sought to bring about the Ireland the Volunteers envisaged, a country of equality, fairness, women’s rights and access to jobs. Placing the spotlight on the experiences of women during this period and their contribution to the events that occurred together with images and descriptions of the daily lives of the so-called ‘ordinary’ people, through exhibitions, talks, film and publications, Cork City has reflected and remembered. Each year during this commemorative period Cork City Libraries have produced a calendar with rarely seen images remembering the city and its people.

While reflecting and remembering, we keep in mind that history is not black and white, and it must not be forgotten. Stories must be told from all sides to allow for reconciliation and healing. With this in mind a national conference ‘The Irish Civil War’ takes place from June 15-18 in UCC with fringe events each evening at the City Library. The aim of the conference is for ‘meaningful engagements with a difficult and traumatic time.’

A list of their past events can be found here.

Cal McCarthy is a former civil servant who currently works in the Michael Collins House Museum in Clonakilty. He is the author, or co-author of five major studies dealing with Irish revolutionary history, penal history, and maritime history. His book Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution, The Collins Press, 1997 was the first book on Cumann na mBan since Cork’s Lil Conlon wrote Cumann na mBan and the Women of Ireland 1913-25.

My interest in Cumann na mBan arose during my research for a 2005 MPhil thesis on the 1918 election. At that time the historiography of Cumann na mBan was somewhat lacking. Although there were a few outstanding studies of Irish women’s history which had examined the organisation from a gendered perspective, there didn’t seem to be anything which was entirely focused on the organisation itself.

I have not worked in the area for almost a decade, and so the recent event served to refresh my memory of many of the more interesting debates that continue within the historiography, as well as of the lives and times of some of Cumann na mBan’s better known members.

While a brief article like this can do little by way of contribution to knowledge, it might be used to enunciate two major issues that the discussion seemed (from my perspective) to highlight.

- How might locally-sourced archival material enhance our understanding of the organisation?

Dan Breen’s presentation on the Conlon archive held at Cork Public Museum, highlighted the richness of one archive that Dan and his colleagues have made accessible to the public. It is very possible that other such archives exist in various smaller museums and libraries all around the country. Though their relevance to Cumann na mBan may not be immediately apparent, it is only through utilisation of such archives by students and professionals, that we begin to understand the depth of source material. In short, the work of local historians is key to enhancement of the Cumann na mBan bibliography.

The more of that work that is done by students under the supervision of John Borgonovo, School of History, University College Cork and his professional colleagues, the more comprehensive and accessible that bibliography will become.

- How might local/self-published histories contribute to the study of Cumann na mBan?

Local histories written and published by local people are quite common nowadays. Some of them are of exceptional quality, some are very poor. The latter category can suffer from a number of common flaws including bias, inadequate citation of source material, and even poor grammatical construction. Oftentimes one suspects that a degree of professional tuition may have addressed some of those issues. In an ideal world, where resources were readily available, local historians seeking to self-publish local history would have access to the advice of a professional supervisor in the same way that postgraduate students do. While it is unlikely that our universities can provide that level of assistance without considerable enhancement of their resources, they may be able to run occasional lectures or symposiums seeking to explain professional standards and methodologies to those who are unfamiliar with same. Those of us who are already partially familiar with same, might also benefit by attending such events.

The utilisation of private source material in such publications often makes them enormously interesting and unique. But the lack of availability of such source material for other historians should be a concern for the discipline. The owners of manuscript collections cannot be compelled to make them available for public consultation. However those of us who work in museums and archives should consider whether we can be more pro-active in the collection of such material. We might also wish to consider whether we can offer any assurances regarding the protection of material which the owner might consider ‘sensitive’ and whether we can communicate a clear policy in relation to such material. As always, most of us lack the resources for such a pro-active approach, and specific funding streams might be considered by government.

These are merely thoughts jotted down in the wake of an interesting discussion on an evolving topic. They are not likely to be unique, and have probably been better articulated and developed by others. An understanding of that development may lead to a better understanding of what is possible, what is not, and what the future of the discipline may look like.

Cal McCarthy, 2022.

Anne Twomey is a graduate of University College Cork. She has a BA in English and History, an MA in History and a H. Dip in Education. She has been working in Adult Education since 1998. Anne is the Adult Ed Coordinator in North Presentation Secondary School in Cork City and teaches History, English and Political Studies on the programme.

Anne is also a member of the Shandon Area History Group in Cork City, a very active local history group. They have been involved in local history exhibitions and published the book Ordinary Women in Extraordinary Times, the story of 11 Cork women during the revolutionary years, for the 2019 centenary commemorations. The group has a Facebook page that has regular posts on local and national history topics. Anne is a regular contributor to the Mother Jones Summer School, Cork. This is a local heritage week and Lifelong Learning Festival. She delivers talks to local history groups around the city and county of Cork. She has also contributed to several documentaries. Her focus is mainly on the contributions of Cork women to the history of their city. The Shandon Area History Group’s most recent project is the Shandon Church Tercentenary 2022. This is a historic commemoration of one of the city’s most iconic buildings.

The Conlon Sisters, and their contribution to Cumann na mBan, Cork, 1913-25.

“they gave of their best in the stormy years ahead and made heroic sacrifices in diverse ways…”

In 1969 Lil Conlon published Cumann na mBan and the Women of Ireland 1913-25, a book that aimed at redressing the dearth of material documenting the role of Irish women in the revolutionary years. The book is primarily a compilation of the undertakings of the Cork branches of Cumann na mBan. The information is drawn from the Conlon sisters’ records and memories, what they had documented over those incredible years. It is, nonetheless, an eyewitness account of sisters who were heart and soul committed to Irish freedom and who drew no distinction between male or female. They saw them all as comrades, called on to serve that cause:

“mothers, wives, sisters, sweet hearts…who were dragged into that cauldron of self-sacrifice where the cost

was not assessed or defined by limitations…to prove that sex was no deterrent in the National fight..”

For us in the Shandon Area History Group in Cork, it was Lil’s hard hitting and passionate introduction to the book that gave us food for thought and inspired us in our own small way to answer her sarcastic and cynical question: “so what did the women do anyway…?” We could hear her Cork voice almost saying, “really lads…really.. do I have to spell it out for ye?” Her obvious hurt was infused by an underlying argument that even in the 1966 commemoration, women like her sister, May Conlon, Kate “Birdie” Conway, Sorcha Duggan and her sisters Peg, Annie and Brid, and many more of their ilk, were basically consigned to the wastelands of history; that beyond a brief nod to a march past the GPO, nothing about the huge contribution of the “ordinary” women to our country’s fight for freedom was really spoken about or even properly documented. According to Lil these were the women:

“organised and unorganised who rendered such gallant and heroic assistance during the years 1913-25

and of whom little or no mention has ever been made”

When I read this, I was struck by the line “no mention has ever been made.”

What made her undertaking so unique was that she was attempting to memorialise these women before they were eradicated by death from living memory. In other words, it was her call to others to follow in her footsteps and write fuller histories of women all over Ireland, like her sister, who had played their part and to do so before they died. She was so conscious that by the 1960s time was running out for many of these women and the poignancy of this is that her own efforts were too late for her beloved sister, May, who died in 1946. All Lil could do was dedicate the book to May and I suppose hope that she and the others “who gave of their best in the stormy years ahead and made heroic sacrifices in divers ways” would be remembered. It inspired us to undertake an exhibition in 2016, highlighting via story boards, the contribution of 11 Cork women to the fight for freedom in our city.

In 2019 we developed their stories into a book entitled Ordinary Women in Extraordinary Times. The reaction of the descendants of these 11 women whose stories were known only to a few, humbled us. We hoped that Lil’s plea for these women to be remembered had in this small way been answered. At the time our 11 women did not include the Conlon Sisters as others were focussing on them. However, it is now our turn in Shandon History Group, to give a brief outline of the activities of both May and Lil during the “stormy years” of the fight for Independence.

Lil (Elizabeth) and May (Mary) were members of the Conlon family from Blarney Street in the heart of Cork’s Northside. Later they would move house to Sunday’s Well but never far from that part of the city which gave its name to the branch of Cumann na mBan that they both founded in January 1918, Shandon Branch. The Conlon family comprised 7 children, 3 boys and 4 girls, and their mother Elizabeth and father Michael. Their father Michael had a steady job as a “tail-pipe man” in the local distilling industry. As a result of his solid income, the family’s economic circumstances coupled with a huge belief in education meant that both the boys and the girls were educated to a high standard. They all became immersed in the social, cultural, sporting and political life of Cork City. May and Lil were close in age, May being born on April 26th 1892 and Lil on 29th of March 1894 and a deep bond developed between them that was to last a lifetime. They shared similar passions in GAA, drama, the Gaelic league, an Irish Ireland, contributing to all these areas in whatever way they could. The formation of Cumann na mBan in 1914 attracted both Lil and May from the outset as a “doing” organisation, somewhere they could actively be involved and not watch from the side-lines, so to speak.

On the 8th of June 1914, a meeting to test the waters in relation to establishing a branch of Cumann na mBan in Cork was held in the City Hall. Among those attending were Agnes Farrelly and Bulmer Hobson. Mary MacSwiney presided over the meeting that launched Cumann na mBan in Cork, with one branch set up called the “Cork” branch. Also involved from the outset were retired opera singer Kate “Birdie” Conway, Magdalen (Mid) Hegarty, wife of a future IRA commander in Cork, Sean Hegarty, several sets of sisters, the Murphy girls from Washington Street, the Duggans from Blackpool and from Blarney Street the formidable May Conlon and her younger sister, Lil. Small beginnings but these women, among others, dedicated themselves to expand the movement across the city and county of Cork. These efforts began to bear fruit from 1918, when branches sprung up around Blarney, Passage, Douglas, Bishopstown, Pouladuff, Cobh, Blackpool, Riverstown, and Mary MacSwiney’s own branch, Poblacht na hÉireann, to mention just a few.

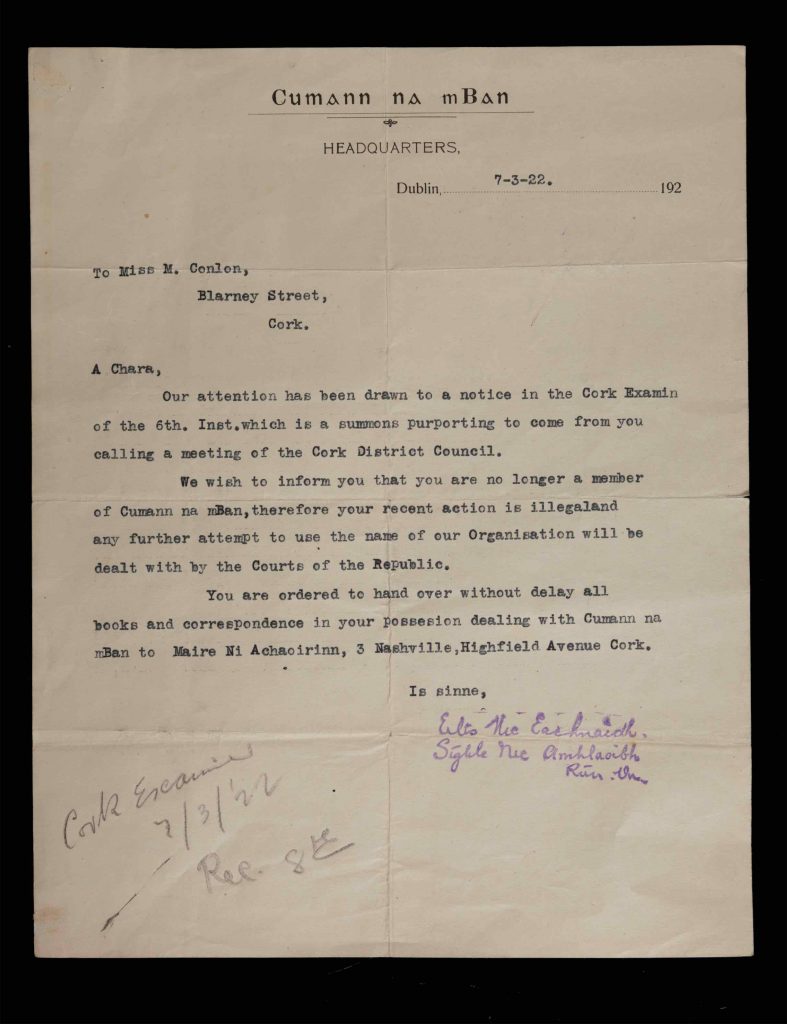

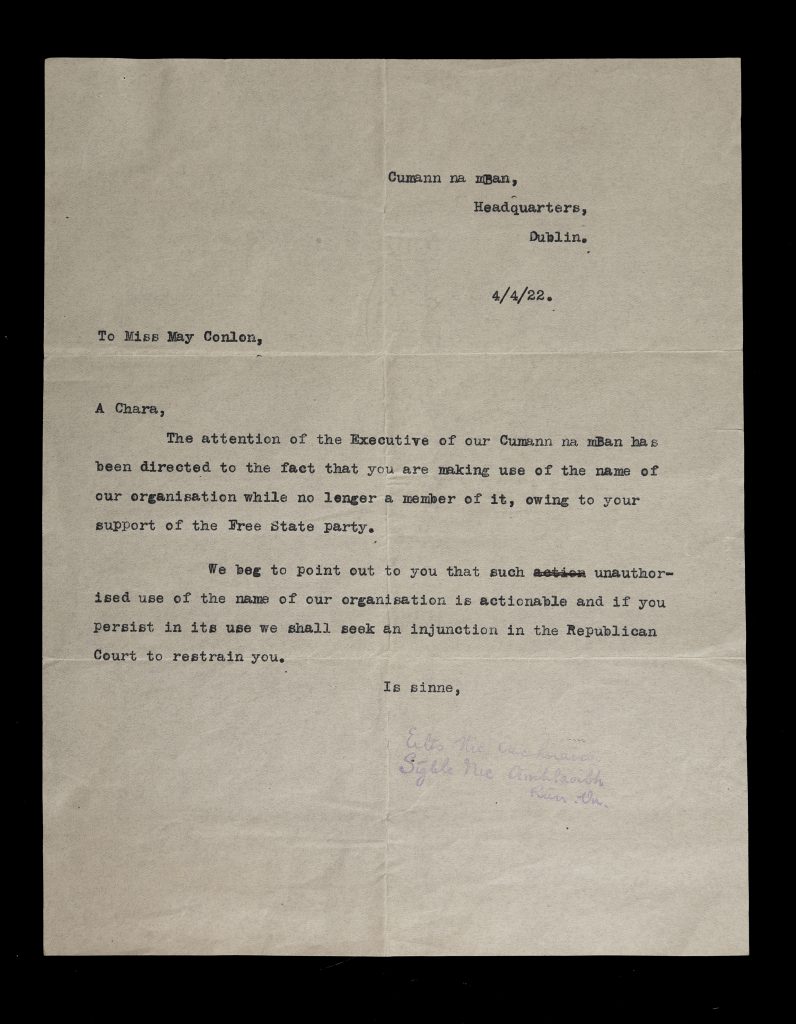

Shandon Branch of Cumann na mBan was established in January 1918. The role of May or as she became known, Bealtaine, was crucial in getting it set up, maintaining it, recruiting others into it and being very active in the Shandon, Blarney St, Sunday’s Well area. Lil herself described the Shandon branch as “one of the most active and enthusiastic branches in the country”. May became a brilliant administrator and was honorary secretary of the branch. Lil never held office in the branch as both she and May thought it was not a good idea to keep too many posts in one family. Instead, Lil served on the committee, but effectively became her sister’s “stand-by…and took over her duties as required”. Lil was instrumental in establishing and teaching the Irish language classes in the branch. As her sister’s confidant, Lil had access to all the minutes of the Shandon Branch and from 1920 on, to those of the Cork District Council, as well as all correspondence and memos of the branch. When the split developed in Cork Cumann na mBan after the Treaty vote, May with the full knowledge of Lil, refused to hand over any of their records and deposited them to a safe hiding place. Years later Lil knew exactly where to go to retrieve those records which formed the core of her research for her book. Of all the members in their group, the sisters became very close to Kate “Birdie” Conway and invited her to be President of the Shandon Branch, where she applied herself to fund raising activities with gusto and used her connections in the musical world to raise awareness of the fight for independence. She would also occupy the same role in the 1922 pro Treaty Cork executive, alongside May. May would later provide a heartfelt and fulsome tribute to Kate in a published obituary in the Cork Examiner in 1936.

The Shandon branch operated in an area of heightened tensions during the War of Independence and later the Civil War. Local Volunteer units were very active in the districts of Sunday’s Well, Blarney Street, Kerry Pike. As a result, they experienced a fair share of attacks, arrests, reprisals, arms storing, and RIC and Black and Tan raids. The women’s gaol was located in Sunday’s Well and as arrests of girls and women increased from 1920 on, the Conlon sisters and their Shandon branch were closely associated with providing provisions, comforts, visits to the female prisoners there. Indeed, May Conlon herself was arrested for distributing pamphlets and was sentenced to a short period of detention in Sunday’s Well Gaol. She knew this would happen and hoped to use the arrest and imprisonment as a propaganda tool for highlighting conditions in the prison.

The Conlon sisters maintained close bonds with the families living in the surrounding areas and recruited from them and supported them in times of trouble. Shandon Cumann were intimately connected with the aftermath of the Ballycannon massacre, the death of Volunteer Denis Spriggs and Fr. O’Callaghan, friend to Liam de Roiste, and aided the delivery of Michael Collins’ body to Sunday’s Well hospital during the Civil War. The intensity of their involvement in the fight for independence shaped their decision as a branch to accept the Treaty and work for its broader acceptance in Cork. They had had too much of violence and were shattered by the killing of Collins to whom they had become very close during the War of Independence and in the early months of the Civil War.

As the War of Independence progressed, so too did the role of the Conlon sisters in Cumann na mBan in Cork. May’s administrative abilities saw her promoted to the role of honorary secretary of the Cork District Council of Cumann na mBan in 1919. She held the post until 1922, during which time the Cork branches upped their commitment and support to the Volunteers in the city and county, providing essential medical care, weapons delivery, pamphlet distribution, collection of monies, provision of prisoners’ dependant funds, food supplies etc. She was also the Cork delegate to the national executive of Cumann na mBan.

May, with the support of Lil and Birdie Conway among others, established the Cork Executive of Cumann na mBan after the split over the Treaty. May became its honorary secretary and was a member of the GHQ of Cumann na mBan. The Conlon sisters were instrumental in pushing for support for the Treaty among the Cork branches. They worked to get a vote taken that would decisively show that Cork Cumann na mBan backed the Treaty. Inevitably this brought them into conflict with Mary MacSwiney and others who had taken a firm anti-treaty stance, in common with many nationwide branches. In February of 1922, spearheaded by the Conlons, Cork Cumann na mBan voted by 16 to 7 to support the Treaty and the efforts of the Provisional Government to establish itself as the legitimate government of the new Free State. The bitter split and dog fight for control over Cumann na mBan that followed in Cork was mirrored across the country in many houses and around many family tables as the terms of the Treaty were everywhere passionately debated. Claim and counter claim to the title of Cumann na mBan were advanced through the pages of the Cork Examiner and other agencies. In these encounters anti-treaty and pro-treaty Cumann na mBan in Cork denounced each other and called on the Cork public to deny one side or the other the right to speak for Cork Cumann na mBan. In April of 1922, May, using her code name Bealtaine Ní Choindealbháin and supported by Siobháin Ní hÉigeartaigh, issued what became known as the Cork Manifesto. It was a call to women in Cork who supported the treaty to stand up and be counted in giving their allegiance to the Provisional Government, in maintaining their right to act as Cumann na mBan and not to be cowed by the anti-treaty Cumann na mBan personnel. They were determined to remain as the voice of Cumann na mBan in Cork, and not to accept the title of Cumann na Saoirse, as other pro-treaty Cumann na mBan branches had done in other counties.

This steadfast support for the Treaty and the National Army of the Provisional government by the Conlon led Cork Cumann Executive, continued until 1925. By that year Lil Conlon maintained that the Government and Army were well established, and it was unanimously decided at a meeting of the executive of Cork Cumann na mBan to:

“… discontinue the Organisation as it was the considered opinion we had conscientiously performed our duty to the Government and the Nation.”

The Conlon sisters did not walk away from involvement in the city they had served during the troubled times. They continued to be involved in the cultural life of the city and were big followers of Cork GAA teams. Indeed, their sister, Kate, helped to bring Camogie to Cork in 1904. Lil worked as a civil servant in Dublin for many years and then in administration in UCC where two of their brothers, Michael and Seán, served on the governing body. May, having worked in the commercial life of the city for many years, retired to the family home, Lee View, Sunday’s Well, as her health was not good. Despite this she involved herself in advancing the missionary work of the Holy Ghost Fathers. Lil, faithful as ever to her sister, took up the role of honorary secretary to the Cork Branch of the Holy Ghost Fathers. Neither sister married, both continued to live in the family home. Failing health took its toll on May and she died on September 2nd, 1946. The death notice paid tribute to her indomitable spirit, her courage and determination. Lil died on 29th of October, 1983 and her obituary noted her deep involvement with the national revival long before 1916. Both sisters are buried in the family grave in the old graveyard of Kilcrea Abbey, County Cork.

In conclusion I return to Lil Conlon’s book and its attempts to record the work of the women of Cumann na mBan. Words she wrote in praise of these women apply equally to May and Lil Conlon themselves, founders of the Shandon Branch of Cumann na mBan, Cork:

“ heroines of history, unsung, unrecorded but none-the-less fulfilling a glorious destiny” .

- All quotations are taken from Lil Conlon, Cumann na mBan and the Women of the Ireland, 1969 Kilkenny People Ltd.

Anne Twomey MA HDE

Shandon Area History Group Cork

Email: [email protected]

Facebook page: https://m.facebook.com/ShandonHistory/